This Journal article is subject to copyright. To cite this Journal article: Gale, J. (2010). Addiction: A Psychospiritual Perspective. The CAPA Quarterly, Journal of the Counsellors and Psychotherapists Association of NSW (4), 20-23 retrieved from https://jodiegale.com/addiction-a-psychospiritual-perspective/

This Journal article is subject to copyright. To cite this Journal article: Gale, J. (2010). Addiction: A Psychospiritual Perspective. The CAPA Quarterly, Journal of the Counsellors and Psychotherapists Association of NSW (4), 20-23 retrieved from https://jodiegale.com/addiction-a-psychospiritual-perspective/

Addiction: A Psychospiritual Perspective

‘In every human being there is a special heaven whole and unbroken’

Paracelsus.

The word ‘holistic’ is used often within the helping professions, yet on deeper exploration, ‘spirituality’ is often neglected. It is not seen as legitimate and is rarely given space in psychology, social work, counselling and psychotherapy training (F. Gale, 2007). Considering global emergencies such as financial and environmental crises, war torn countries and displaced peoples, the widening gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian’s health and well-being, levels of addiction to the internet, food, drugs, alcohol, gambling, sex and shopping and a growing sense of disconnection from self and others – neglecting a spiritual context continues to have dire consequences for individuals, communities and the ‘whole’. ‘Outcomes based’ medical models supported by many governments are primarily concerned with ‘getting rid’ of problems rather than caring for the whole person (WHNSW, 2002). Yalom sees that our field is in crisis due to economically driven, perforce symptom orientated, brief, superficial and insubstantial therapies (2002, pg. xiv). In ‘Healing the Split’, John Nelson (1994) suggests that no area of Western thought is more in need of the input from spiritual disciplines than our understanding of [neuroses] and psychoses. Wilber (1994) writes,

‘First spirit, then soul then mind were rejected by modern psychology and psychiatry, with the disastrous result that men and women were nothing more than sophisticated bundles of material atoms in vaguely animate bodies. Thus our modern ‘science of the soul’, almost from the start has been a science merely of the physical and bodily components of the entire human being – a reductionistic cultural catastrophe of the first magnitude…transpersonal psychology has reintroduced the dimensions of soul and spirit’ (pg. ix).

What is Spirituality?

Spirituality in this sense is not synonymous with religion, although it could be for some. In psychosynthesis – the model I use for holding a spiritual context – the spiritual Self (capital S), is considered the source of our being, a spark of the Divine – the innate drive that continuously calls us towards growth and wholeness. The Self is made up of will and consciousness – it is our life force. When connected to our deeper essence, it provides a way of understanding and finding value, meaning and purpose out of our suffering.

Assagioli and Psychosynthesis

Roberto Assagioli (1888-1974), was a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, colleague to both Freud and Jung. Although useful to discovering the human psyche, he felt that psychoanalysis alone was limiting to clients in that they were often pathologised and reduced to their symptoms and history. He was interested in the soul, the esoteric, yoga, and religious teachings such as Jewish Mysticism, Buddhism and Christianity; these deeply influenced his map of the human psyche (Young-Brown, 2004).

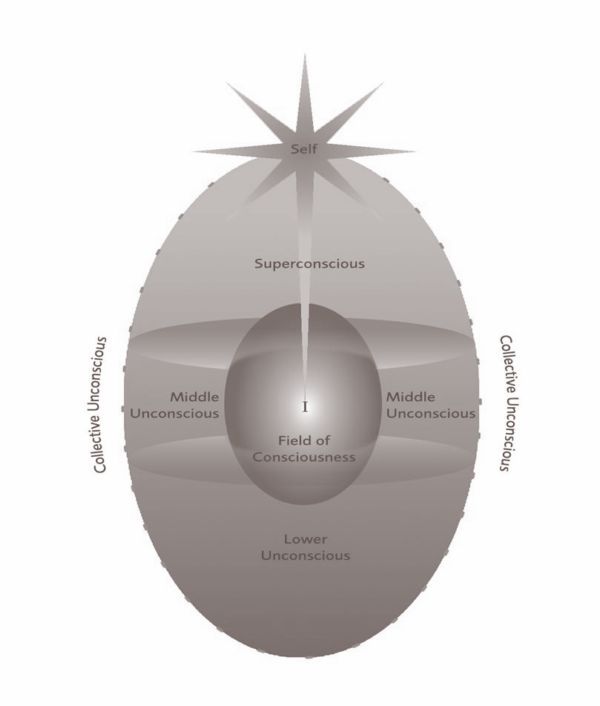

Assagioli’s work has been widely influential in the fields of humanistic, transpersonal and mindfulness based psychologies. Psychosynthesis integrates the best of western psychology, eastern and western spiritual disciplines. The psychosynthetic model of consciousness is in a constant process of evolution and growth as rigorously trained practitioners worldwide integrate new philosophies and ideas – such as neuroscience – into their theory and practice. Assagioli’s model is still at the cutting edge of psychology today due to its inclusive nature and because it takes into consideration the whole of the psyche. The ‘Egg Diagram’ (IOP, 2006) represents this:

One analogy we use in psychosynthesis is that of a house. In the basement, we work with the lower unconscious energies, using theories and techniques of psychoanalysis and object relations. On the ground floor, the middle unconscious, the work is predominately in the ‘here and now’ incorporating humanistic and existential theories and techniques. In the loft, the Superconscious or higher unconscious, we work with the spiritual and transpersonal theories and techniques of Assagioli, Jung, Grof and Wilber. Throughout a session, we dip in an out of the different levels of the psyche exploring our clients history (past), the here and now (present) and the immense potential for healing (future).

In psychosynthesis, ‘Self’ is an ontological reality. The first expression of Self is through the ego. Once healthy ego development is achieved, Self becomes more ‘itself’ through the gradual awakening of the ‘I’. Sorrell (2009) writes, ‘the “I” refers to the “observing self”, the part of us that appears to watch the world, others and ourselves with interest rather than with judgement’ (pg.11). The ‘I’ is made up of consciousness and will. It is transcendent yet immanent (Firman & Gila, 1997). Things get sticky when the ‘I’ becomes identified with the parts and functions of the ego/personality. The aim of psychosynthesis is to free the will from identifications within the personality and for the ‘I’ to be in direct connection and identification with Self.

Bifocal Vision

Clients suffering with addiction are more than their pathology; they are a Self on a bio-psycho-socio-cultural-sexual-spiritual journey. The therapist holds the context that at the core, we are ‘whole and unbroken’, not diseased, sick or in need of a cure. We perceive ‘the client as a Self, a being with a purpose in life and with immense potential for love, intelligence and creativity…also as a personality, an individual made up of a unique blend of physical, emotional and mental characteristics’ (Whitmore, 2000, pg. 70).

Addiction: a symptom of psychospiritual crisis

Christina Grof (1993) proposes that addiction is a spiritual crisis. Stanislav Grof, a pioneer of transpersonal psychology together with Christina, claims that there are three major categories of spiritual crisis:

1) Biographical, due to disturbances in primary attachment relationships, childhood trauma and/or abuse in our history.

2) Perinatal, which occurs around the time of birth and incarnation – these have to do with existential, being and non-being energies.

3) Transpersonal, which are to do with transcendence of the ordinary boundaries of the personality – or could be to do with the occult, mystical, religious and paranormal experiences (1989, pg. 8-9).

Akin with Jungian theory, the psychosynthetic paradigm ‘views human development as following a spiral course of departure from and higher return to the origins of being’ (Benson, 2003, pg. 124). Grof (1993) suggests that we begin to disengage from the sea of spirit at conception, leading to estrangement from our Divine roots as our essence becomes contained into matter. She warns us that when wounding occurs in childhood, for example when the authentic self isn’t mirrored or when it experiences annihilation, it reinforces the earlier experiences of separation from the whole and our sense of isolation deepens and becomes cemented into place. Addiction, from this perspective, is a way of managing these biographical, existential and spiritual crises (J. Gale, 2008). Furthermore, Grof and Grof (1990) suggest that ‘all addicts experience an internal loss, a spiritual bankruptcy or soul sickness that cuts them off from the world around them. They enter the soul’s dark night and wrestle with the demons of fear, loneliness, insanity and death that are so common in spiritual crisis. Thus begins a search, a longing, a thirst and a hunger for spiritual (re)connection and identity. The problem is that the client searches for relationship, connection and spirit in all the wrong places. ‘Using’ is not just to numb pain experienced through biographical trauma and wounding. Clients also use their drug of choice to search for spiritual qualities: connection through texting, validation and acceptance through Facebook status updates and ‘Friends’, love and soothing in food, and perhaps joy, goodness or confidence when using drugs or alcohol.

Clients come to the therapist’s door often drowning in a sea of despair, rage and shame. They either ‘act out’ through their addiction or ‘act in’, turning the feelings inwards (C. Grof, 1993, pg. 79), creating further crisis and providing more fuel for the addiction. They come wanting a ‘fix’ for the problem but at the core they believe ‘I am the problem’. If we only see the addiction as something to get rid of, to fix or to cure, we are reducing clients to their symptoms. Susie Orbach writes, ‘we don’t produce symptoms unless we have no other route to express distress…if we remove it without exploration, we usually produce a symptom switch’(1988, pg. 146). Therefore we need to search for the value, meaning and purpose hidden within the addiction. In psychosynthesis we ask, ‘how is this addiction serving the client?’ and ‘what is the Self calling for this person to awaken to through their addiction?’ Asking these questions will lead us to the soul’s suffering, to that which is missing in our clients’ lives and relationships. We need to be able to sit with deep suffering; this facilitates clients being able to bear their own suffering. When they can do this, they don’t need to bolt from their feelings, they can stay present to the ‘here and now’ (Roth, 2010).

Maintaining cycles

Clients suffering with addiction are ‘caught in a compulsive pattern that seeks to establish self worth in the face of worthlessness. It is a vicious cycle in which they seek the higher unconscious, fall into the lower unconscious and seek the higher unconscious again. A Buddhist might call this a cycle of aversion and craving. This is a common experience in addiction, a moving from the euphoria of the addiction into remorse and worthlessness, only to begin the cycle again. The tragedy, of course, that the positive qualities ultimately remain out of reach and unintegrated’ (Firman & Gila, 2002, pg. 161-162).

The addiction is fuelled by destructive ‘maintaining cycles’ made up of defences such as rationalizations, justifications and denial – all cleverly set up to keep clients away from their suffering. The work here is about recovering the split-off and deeply buried parts of the client, while at the same time respecting the behaviours, defences and mindsets because these have helped them to survive. So psychosynthesis counsellors would work here to free the will from the maintaining cycle of addiction. By that, I don’t mean ‘Victorian’ will – in psychosynthesis we see that we have strong will, skilful will and goodwill – and that each of these needs activating (Assagioli, 1974). We work to free the ‘I’ from identifications with the false self and the ‘parts’, for example: subpersonalities like the ‘victim’, ‘perfectionist’, ‘saboteur’ and ‘inner critic’, as well as disidentification from feelings, mindsets and historical wounding. This is about a move from ‘no will’ to ‘I have will and choice’. This is often a time of much suffering, as clients disidentify from old identifications and make way for new modes of being. Freedom from the constraints of the personality pave the way for the ‘I’ to be in relationship with transpersonal qualities and the Self. Clients begin to see that they are indeed ‘whole and unbroken’, not a part-object or diseased. At this stage on the journey it is about acceptance of self and surrender to the spiritual Self. The following psychosynthesis meditation is used to disidentify from the parts and to identify with the whole:

I have a body and I am more than my body

I have feelings and I am more than my feelings

I have a mind and thoughts and I am more than my mind and thoughts

I am I, a centre of pure self-consciousness and will

(Assagioli, 1965)

Call off the search

The search for spirit (whatever ‘spirit’ may be for each of us) begins as a healthy impulse towards connection. If we don’t feel connected to our spiritual source, we either numb the pain or search for connection. We search for soothing, for love, for the Divine, not realising we are Divine. We often see ourselves as part-objects and deprive ourselves of goodness – this is especially true for our clients who suffer with addiction. Even when we awaken to our spiritual journey, we talk about God, Spirit, Allah, Buddha, Higher Power or qualities of the transpersonal like worth, beauty and love as though they are something to reach for, ‘up there somewhere’, something only ‘fixed’ or enlightened beings are entitled to. The realisation that ‘I am already the Self that I am seeking to become’ is the ultimate purpose of psychosynthesis.

Staying connected

In the first session, I always ask my clients, ‘What sustains you in life – what makes your heart sing?’ Connecting with physical, emotional, mental, sexual and spiritual hungers and passions provide hope and a context for the work. For some, connecting to spirit might be through mindfulness, meditation or prayer, 12-step community or a group to do with one’s passions. For others, it could be story-telling, gardening, standing on the top of a mountain, connecting to the land or listening to soul music. For clients caught in the ravages of addiction, it is about finding new, healthy and meaningful ways to satisfy and nourish the cravings of the soul and the spirit. Staying connected means constantly asking, ‘am I responding to the invitations sent from the Self?’ We may as well – as it brings great detriment to repress the sublime – the spiritual Self will nag and pull at us until we acknowledge its presence and allow it to be expressed for the common good of the whole (Sewell, 2005).

The gift of therapy

In psychosynthesis, we see that counselling and psychotherapy form a sacred space for the (re)discovery of the Self. It is a place for clients to (re) connect with the heights and depths of their being. A place where they can slow down and be. The psychosynthesis therapist seeks to provide an environment filled with love, compassion, and empathic connection, where over time, the client can blossom and become whoever it is that they were meant to be!

References

Assagioli, R. (1965). Psychosynthesis. London: Thorsons.

Assagioli, R. (1974). The act of will. England: Platts.

Benson, J. (2003). Transpersonal and psycho-spiritual psychology. In Simanowitz & P. Pearce (Eds.), Personality development. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press.

Firman, J., & Gila, A. (1997). The primal wound. New York: State University of New York Press.

Firman, J., & Gila, A. (2002). A psychology of the Spirit. New York: State University of New York Press.

Gale, F. (2007). Introduction: Spiritually sensitive helping practices. In F. Gale, N. Bolzan & D. McRae-McMahon (Eds.), Spirited practices: Spirituality and the helping professions. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Gale, J. (2008). Call off the search: Eating disorders, a symptom of psychospiritual crisis. Middlesex University, London.

Grof, C. (1993). The thirst for wholeness: Attachment, addiction and the spiritual path. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Grof, S., & Grof, C. (1989). Spiritual emergency: Understanding evolutionary crisis. In S. Grof & C. Grof (Eds.), Spiritual emergency: When personal transformation becomes a crisis. New York: Penguin Putnam.

Grof, S., & Grof, C. (1990). The stormy search for the self. New York: Penguin.

Muktananda, S. (1979). Kundalini: The secret life. New York: SYDA Foundation.

Nelson, J. (1994). Healing the split: Integrating spirit into our understanding of the mentally ill (Revised ed.). New York: State University of New York Press.

Orbach, S. (1988). Fat is a feminist issue. London: Penguin.

Roth, G. (2010). Women, food and God. New York: Scribner.

Sewell, M. (2005). Repression of the sublime Retrieved 25th February, 2008, from http://www.uuworld.org/spirit/articles/1837.shtml

Sorrell, S. (2009). Depression as a Spiritual journey. Ropley: O Books.

Whitmore, D. (2000). Psychosynthesis counselling in action. London: Sage.

WHNSW (2002). The nature of women’s health: past, present and future. Leichhart: Women’s Health NSW.

Wilber, K. (1994). Foreward. In J. Nelson (Ed.), Healing the split: Integrating spirit into our understanding of the mentally ill (Revised ed.). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Yalom, I. (2002). The gift of therapy. London: Piatkus Books.

Young-Brown, M. (2004). Unfolding Self: the practice of Psychosynthesis. New York: Allworth Press.