Photo: Cristina Gottardi

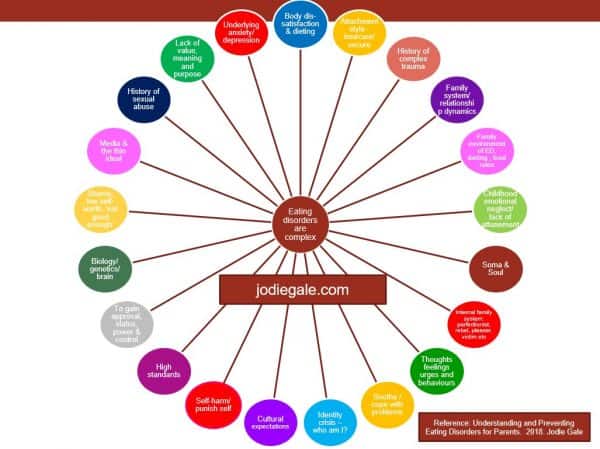

Eating disorders are like puzzles; complex and multifaceted

Eating disorders, disordered eating and other food, weight and body image concerns are complex and multifaceted; each individual has her own unique story and puzzle of risk factors to do with why her disordered eating started, as well as an assortment of reasons regarding its maintenance; what starts an eating disorder, isn’t always what keeps it going.

In my eating disorder treatment work with women, I take a soul-centred, holistic and whole person approach (as opposed to a disease, illness or medically orientated perspective). Whilst the following infographic is not exhaustive, these are some of the underlying and maintaining issues we might work through along the individual’s path to full recovery.

In December 2018, the Australian government announced that those suffering with severe eating disorders will receive 40 sessions of Medicare funded psychological eating disorder treatment as of September 2019. This is fantastic news for some but somewhat limiting for others.

The primary modality prerequisite for Medicare funded eating disorder treatment is Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and Enhanced Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT-E). This type of therapy predominantly focuses on changing thoughts, feelings, urges and behaviours.

There are two major concerns that counsellors, psychotherapists and experts within the eating disorder field have about this:

1. A recent study of the Medicare Better Access Scheme, by the Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry found that the large increase in the use of mental health services after the introduction of the Medicare Better Access Scheme had no detectable effect on the prevalence of very high psychological distress or the suicide rate of the Australian population. Anorexia has the highest rate of suicide amongst all ‘mental illness’.

2. CBT has been heroed as an economical, quick fix solution with a large evidence base for issues such addiction, anxiety, depression, and eating concerns. However, long-term, there is a less than a 50% success rate in eating disorder treatment recovery.

Women’s Health NSW states that ‘outcomes based medical models supported by many governments are primarily concerned with ‘getting rid’ of problems rather than caring for the whole person (2002).

One of the world’s most highly regarded psychotherapists, Irvin Yalom, sees that our field is in crisis and describes these medical modalities as economically driven, perforce symptom orientated, brief, superficial and insubstantial therapies (2002, pg. xiv).

As part of an overall treatment plan, CBT is very useful; I use it as a tool regularly in my work when counselling clients. In terms of my own recovery over 20 years ago, I attended an eating disorder self-help group in London where CBT-E was the primary modality. Then the real work began.

As you can see from the above infographic, eating disorders are far more complex than merely refeeding (if required) and working with cognitive distortions and behaviours.

In 20 years of private practice counselling women with addiction, anxiety, depression and eating disorders, almost every single one of them has had a history of complex trauma.

In Australia, one in four adults – approximately five million people – are estimated to have experienced significant trauma throughout childhood. This trauma occurred in their home, family, neighbourhood, or within institutions (Kezelman et al., 2015 cited in Understanding Trauma, Blue Knot Foundation).

Complex trauma is a significant risk factor for the development of an eating disorder.

What is complex trauma?

Trauma expert Bessel van der Kolk states,

‘The traumatic stress field has adopted the term “Complex Trauma” to describe the experience of multiple and/or chronic and prolonged, developmentally adverse traumatic events, most often of an interpersonal nature and early-life onset. These exposures often occur within the child’s caregiving system and include physical, emotional, and educational abandonment, neglect and abuse beginning in early childhood.’

The National Institute of Mental Health (USA) defines childhood trauma as,

“The experience of an event by a child that is emotionally painful or distressful, which often results in lasting mental and physical effects.”

In Understanding Trauma and Abuse , the Blue Knot Foundation advise that complex trauma is often unintentionally perpetuated by parents who have their own history of trauma. The trauma is ongoing, repetitive and results in the inability to emotionally regulate and to feel safe in the world. The use of coping strategies such as co-dependent relationships, addiction, disordered eating and self-harm are prevalent in those who have suffered trauma.

Complex trauma can appear in many forms and is made up of one or more of the following:

- Abandonment, neglect and abuse (emotional, cultural, physical, sexual, spiritual)

- Attachment related injury resulting in anxious, ambivalent or a disorganised insecure attachment

- Lack of attunement and unavailability to the child’s feelings and needs by primary caregivers which result in emotional dysregulation and a lack of trust that needs will be met

- Primary caregivers’ feelings and needs took precedence over the child’s resulting in narcissistic wounding (and the child is never fully ‘seen’ in her own right)

- Arrested development of the self, a loss of self or poor sense of self-identity

- Deep sense of shame and guilt

- Profound sense of low self-esteem and low-self worth

- Frequency of dissociative and somatic symptoms

- Learned to rely on external rather than internal cues

- Toxic familial relationships, a dysfunctional family system and divorce

- Certain parenting styles such as inconsistent, perfectionistic, critical or smothering/invasive

Trauma interferes with neurobiological development and because early experiences occur in the context of a developing brain, neural development and social interaction are inextricably intertwined (van der Kolk, 2014).

Seubert & Virdi (2019), propose that trauma results in excruciatingly painful and negative stories that build over time. The stories go something like this: ‘I’m not good enough’, ‘There is something wrong with me’, ‘I have no worth’, ‘No-one will love me if I am fat’, ‘I’m unlovable’.

There are many ways that people can distract themselves from the psychic and somatic pain associated with trauma. Catanzaro, Doyne and Thompson (2019) state that one way of doing so is to become obsessed and preoccupied with food, weight and attempts to control the body to the extent where an eating disorder becomes the individual’s primary relationship.

Why eating disorder treatment needs depth psychotherapy more than ever before

Not all individuals who suffer with an eating disorder have a complex trauma history, however, as mentioned previously, many do.

An individual with a ‘severe’ eating disorder, most likely has severe attachment related injuries. This is a deep trauma to one’s core self; a soul trauma. To fully recover from an eating disorder, the individual requires more than medically orientated eating disorder treatment, she needs holistic care that focuses on body, feelings, mind & soul!

With increasing evidence to support the link between eating disorders and complex trauma, symptom orientated, one dimensional treatment is not going to cut it. To quote one of my clinical supervisors who is a world-renowned eating disorder specialist, ‘Well I hope these 40 sessions aren’t going to be more of the same… because that won’t work!’

Jean Petrucelli (2019), in relation to the interpersonal treatment of eating disorders, writes,

‘…an ED symptom is not something to simply get rid of, but rather something to profoundly understand as it holds dissociated parts of oneself and one’s relational history. It reflects aspects of one’s history that cannot be tolerated as part of the self…’

In Why Love Matters, How Affection Shapes the Baby’s Brain, Sue Gerhardt proposes that for an individual who has experienced disturbances in her early attachment relationships and family of history – through psychotherapy – she can grow a socially and emotionally intelligent brain. Gerhardt writes,

‘The missing experience of having feelings recognised and acknowledged by another person, particularly of having strong feelings tolerated by another person is provided by the therapist… slowly through these types of experiences with a psychotherapist, a new muscle develops, an ability to be heard and to listen, to listen and be heard…Psychotherapy offers a change to rework the emotional strategies but it takes time to establish new networks in the brain (2004, p.205).’

Trauma and eating disorder recovery work requires deep, long-term, at least weekly therapy (sometimes 2-3 times a week) with a highly experienced therapist who can use the therapeutic relationship to heal the underlying insecure attachment and early childhood relational disturbances.

In the Centrality of Presence and the Therapeutic Relationship in Eating Disorders (2019), Carolyn Costin writes,

“A positive therapeutic relationship provides a corrective emotional experience, providing healthy attachment, which fosters trust, safety and the ability to facilitate unmet attachment needs….”

Carolyn goes on to say,

‘Repeated experiences of [the therapist’s] presence regulate the client’s nervous system, create neural pathways, and enhance the client’s ability to feel safe, allowing for deep therapeutic work and healing (Geller & Greenberg, 2002; McCollum & Gerhart 2010).’

Most individuals arrive at the therapist’s door drowning in a sea of despair and are desperate for immediate results but recovery requires connection, consistency, safety, security and trust – all experiences the individual may have missed out on. Over time these experiences are internalised to form a secure sense of self.

To quote Jean Petrucelli (2019),

‘Although the eating disorder population wants immediate results, recovery involves a long-term therapeutic approach. This can be difficult to sell when social trends are at odds with participating in meaning-centred, long-term therapy. Through texting, tweeting, swiping and Skyping, the concepts and experiences of sitting with feelings, holding thoughts, and delaying gratification, are challenged as obsolete modes of being, doing, or operating in the world. The irony is that these individuals wish to control their lives, and, paradoxically, to be fully in control, one must learn to relinquish control and find a way to tolerate life’s ambiguities.’

Depth psychotherapy, with someone specifically trained in trauma and eating disorders, is the perfect place to do that.

With the increasing number of individuals suffering with childhood trauma related eating disorders, we need depth psychotherapy more than ever before.

How to find a specialist in eating disorders and childhood complex trauma

Trauma has become a bit of a buzz word. It doesn’t matter which way you look, ‘trauma informed’ and ‘trauma sensitive’ practitioners, services and even schools, are popping up everywhere. Being trauma informed or trauma sensitive is fantastic and it’s great that there is a buzz around it – however – that doesn’t mean all mental health and wellness practitioners can or should be working with trauma. Working with deep rooted, attachment related disturbances, early childhood emotional neglect and complex trauma is highly specialised work and should be with a counsellor or psychotherapist trained to work at depth. It is extremely dangerous to dig around in early childhood wounds if the practitioner does not have specific training to hold the individual in their deep suffering; it can be retraumatising.

I recently wrote an article, What your doctor doesn’t tell you about how to choose a therapist, in addition to this, for your own psychological safety, search for the following when choosing a (psychotherapeutic) counsellor or psychotherapist:

- The depth and length of the counsellor or psychotherapist’s training should be at least 4 years; some psychotherapy trainings can take as long as 8 years.

- Has the therapist had her own, long-term depth psychotherapy? This is crucial – therapists must have worked through their own trauma history and attachment related injuries, otherwise this can interfere with the therapy

- Does the counsellor or psychotherapist have specific training in complex trauma?

- Does the counsellor or psychotherapist have specific training in eating disorders?

- What is the counsellor or psychotherapist’s work experience in ED&T?

- Is the therapist registered with a counselling and psychotherapy federation? In Australia, check your therapist is registered with PACFA or ARCAP.

- Is the counsellor or psychotherapist in at least monthly clinical supervision for the duration of her therapy career?

An individual seeking treatment for an eating disorder needs and deserves to have the type and length of treatment that suits her own individual needs. Currently, depth psychotherapy with highly trained psychotherapists who are also specialists in the field of complex trauma and eating disorders are not offered as a resource for individuals seeking treatment via government funded services. PACFA has recently made a submission to address the shortfall.

For parents and loved ones

If you are a parent or a loved one of an individual suffering with an eating disorder, reading the above about early childhood emotional neglect and complex trauma might trigger some very painful feelings. As a therapist who also works with families of those suffering, this is not about blaming family members because they have likely suffered adverse childhood experiences themselves. For the young women I counsel in my practice, those who recover faster and long-term, have parents who are willing to engage with all of the above, who are willing to spend time in self-reflection and in family therapy (a systems approach). You may stumble across parenting groups where there is a strong allegiance to eating disorders being a biological disease – genetics are part of the overall puzzle – genes load the gun but it’s the environment that pulls the trigger.

5 Responses

Jodie, I love your infographic.

As you have articulated so well, good, effective therapy requires so much more than changing thought patterns. It must embrace and support the whole of a person; and in many cases include good, solid trauma work.

Thanks Toni x

As an victim myself. I can’t agree with you more. It took me over a decade to get better , even now, I can still see how I was still effect by it. It literally destroys my life. So I really appreciate your efforts into this. Ed can lead to great harm in one’s life and it’s complex and need deeper therapy.

Hi Jodie,

I really want to thank you for this thoughtful post. I am in my 40s now and suffered from anorexia and later bulimia as a teen. Thankfully I was able to fully recover but only after being able to connect with and express my feelings related to family difficulties and trauma. I feel so much that is out there these days about eating disorders is so very shallow and misguided. People suffering really need exactly the kind of thoughtful, compassionate approach that you are advocating. Thank you so much for this posting!

Thank you so much for your feedback -I really do appreciate it. Wonderful to hear that you have fully recovered. x Jodie